Automation, Trade, and Friedman's Car Crop

2023 May 28

Economists tend to be very enthusiastic about international trade. Ricardo is most famous for this, but I think most of them have the same inclination. Economist David Friedman has an interesting argument for how it can be that tariffs cause harm, not only to foreign industry, but also to those local industries that aren't amongst those favoured by the tariff:

If you still find the claim that tariffs on Japanese automobiles are a way of protecting us from the Japanese in order to keep American workers from being replaced by Japanese workers plausible, consider the following fable.

Growing Hondas: There are two ways we can produce automobiles. We can build them in Detroit or we can grow them in Iowa. Everyone knows how we build automobiles. To grow automobiles, we begin by growing the raw material from which they are made--wheat. We put the wheat on ships and send the ships out into the Pacific. They come back with Hondas on them.

From our standpoint, "growing Hondas" is just as much a form of production--using American farm workers instead of American auto workers--as building them. What happens on the other side of the Pacific is irrelevant; the effect would be just the same for us if there really were a gigantic machine sitting somewhere between Hawaii and Japan turning wheat into automobiles. Tariffs are indeed a way of protecting American workers--from other American workers.

A very neat and clever argument. If some inventor comes up with a magic machine that transforms wheat into cars, they are celebrated as a genius and we don't ban the machine or slap a heavy tax on it. "Same with trade" says David Friedman.

As with all claims in economics, it's very important not to be too "spherical cow" about this. In some rare cases there might be legitimate reasons to institute tariffs. Many industries display path-dependence so that temporarily protecting one with tariffs when it's first getting started allows it to survive and mature to the point where the tariff is no longer necessary.

But it's certainly true that tariffs and other protectionist measures seem to be net-harmful in most cases. For example, take the Foreign Dredge Act, or the Jones Act.

Interesting side note, one thing that makes these cases particularly egregious is that they fully ban the use of non-American ships. Subsidizing American-built ships would have been much less bad, since the whole system safely fails to the default outcome (importing ships) once building ships in America becomes too expensive even with the subsidy. With a ban, on the other hand, we're stuck being unable to ship things back and forth within the country.

This points to a rule of thumb for policymakers: In cases where it seems like some amount of protectionism really is necessary, subsidies are better than tariffs, which in turn are at least better than outright bans. The great thing about subsidies is that it's fairly easy to notice that you're mailing out checks every month. If the subsidy stops doing any good, then during a cost-cutting phase some enterprising politician can come along, notice that the program doesn't seem to be buying much of anything, and shut off the bleeding. It is (from a government's perspective) a lot harder to notice that you've accidentally crippled domestic shipping, and so here we are a hundred years later, still bleeding.

End of side note, and I'll now start saying some things more sympathetic to the protectionist side of the story.

But first, Andrew Yang! Yang was a democratic candidate in the 2020 US presedential elections. Though he never got close to winning, he did have some interesting ideas about automation, the kind of thing that it's unusual to see discussed in mainstream politics. Yang's theory is that automation is coming for all of our jobs. The manufacture of many kinds of goods is already heavily automated. Yang asks: What happens when we have self-driving cars and trucks, replacing the jobs of drivers? What happens when OpenAI builds a GPT good enough to replace all the programmers and lawyers? What happens when we have robots that build and maintain buildings for us? There might be a handful of jobs left, but they're not likely to compose much of the economy. And without jobs, how will people be able to eat? Do most humans just become redundant at that point? Will we be turned into food for the genetically engineered carnivorous horses of the rich? Yang's idea is that we should adopt a universal basic income so that everyone can still live, even if they can't find a job because of automation. Of course, this is only half the story, the other half being the question of how a universal basic income could be funded. Is universal basic income even a good idea? Let's try to answer these questions.

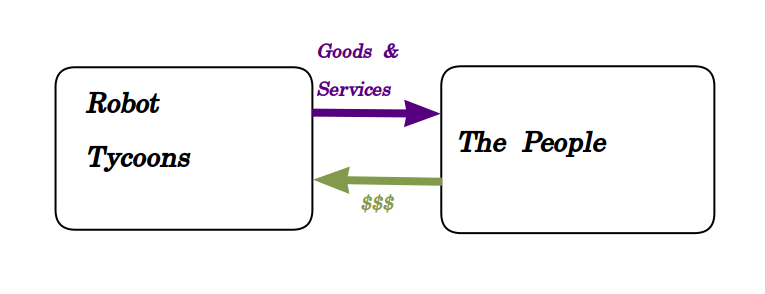

Thinking in limits is often a good way to get intuition about a system. Take the limit where everything can be automated, and there's no use for human labour at all, because robots perform all necessary tasks. The scenario we want to avoid is one where the owners of all this machinery become fabusously wealthy, while ordinary people are made redundant. Here's a very rough diagram of an economy where big companies with robots produce all goods and services:

As drawn, it depicts an inherently unstable economy: Money flows only in one direction, so the people will eventually run out of money, and stop being able to pay for things. Can we avoid this problem? One way to avoid it is to make everyone into a robot tycoon. If these companies are publicly traded, then it should be possible for anyone to buy their stock. Then if the stock pays dividends, that should provide enough money for people to be able to afford to buy robot-produced goods.

Unfortunately, it just seems to be empirically true that stock ownership is very unevenly distributed, and this will probably also be true for robot companies. The reasons why someone may end up without shares in a robot company are numerous: The company may not be public, or it may be public but with shares that are difficult to buy for citizens of some countries, plus many people will be too poor to be able to afford to buy stock, plus babies aren't born owning stock and when they grow up they would have difficulty earning the money to buy it in a world with no jobs, plus some people will find it difficult to filter out sensible advice that anticipates the automation trend from the thousands of investing scams that plague the world.

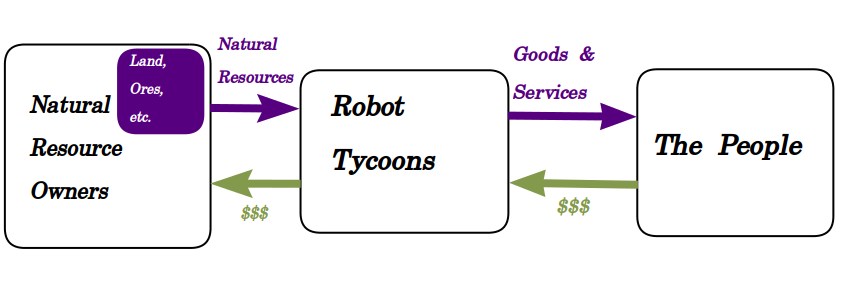

A second problem is that no company will pay 100% of its income to its shareholders. It may have a few residual employees like the executives, plus it may buy some services from other companies. So customers will pay more money to the company than it pays out in dividends. This money goes to execs (who will thus be able to consume far more than most other people), other companies (hopefully also publicly traded, or else their private owners will be able to consume far far more than most other people), plus also resource costs, for the metal ore, solar energy and other natural resources that power the automated future.

Now assume a competitive economy. Which of the following outflows of money from a company will be the largest?

dividends | payments to other companies | payments to natural resource owners | executive salaries

The one we can't be sure of is payments to other companies. It depends how consolidated the robot companies are. But if we lump all the robot companies together into one big chunk so that we can ignore payments between them as purely "internal", then of the remaining three options, we should expect competition to force executive salaries and dividends to be as low as possible. After all, a company that paid fewer dividends and paid its executives less could offer a better price for the goods it produced, and would thus be able to grow at the expense of companies that spent more on these things.

If we're assuming that people are going to be suriving off of dividends, this is terrible news! Nearly all the spending is going towards natural resources!

So, continuing our game of "follow the money", where is the money being spent on natural resources going? It's going to the owners of those resources, of course. The owner of a mine gets paid for ore, the owner of a chunk of sunny desert gets paid so that someone can install a solar farm on the land.

So if all these natural resources are privately owned, then that's how the instability pans out. Eventually all the money drains from the general population to the big owners of natural resources, and the robot companies are merely a pipe through which this money flows. If ownership of the sunny land where solar farms are located is concentrated in the hands of a few big owners, then everyone's monthly electricity payments are going to constitute an unbalanced outflow which they can't balance by employment because there are no unautomated jobs left!

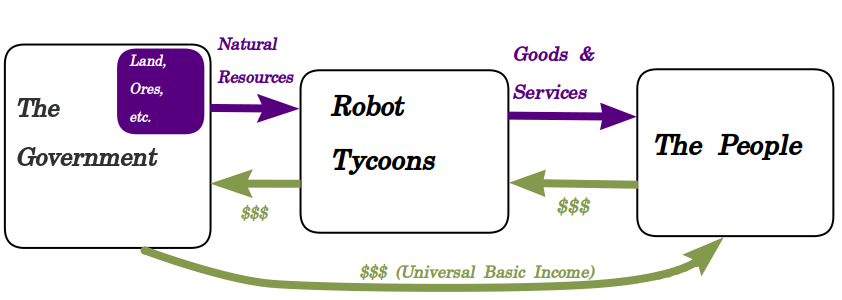

This is where Georgism comes in. Georgism is an economic theory which says that natural resources should be commonly owned (eg. nationalized). It's distinct from communism which says that the means of production should be nationalized. The means of production could be construed to include natural resources, but it also includes far more, eg. factories, farm equipment, etc. The obvious objection to communism is that factories don't just come into existence. They need to be built by workers and those workers need to be paid. The usual way this is done is that an investor will pay the workers now because they'll later get to own the factory when it's finished. If factories were instead nationalized upon completion, there'd be no reason for an investor to pay people to build one. This objection doesn't carry over to Georgism, though! The whole thing about natural resources is that they're naturally occurring. If you pay rent to people for owning land, that doesn't increase the total amount of land. Similarly, if you nationalize land ownership, that doesn't reduce the total amount of land. Georgism doesn't propose that the solar farm in our example should be commonly owned. It proposes that the land it's built on should be commonly owned. The solar farm owners still get their profits from selling electricity. But instead of paying rent to some random dude who happens to own that chunk of land, the solar farm owners instead pay the government, which distributes that money to everyone, since the land is commonly owned.

This constitues a kind of universal basic income, since the proceeds from natural resource ownership are distributed equally to all citizens. Crucially, it's funded by selling access to natural resources, and tied to the price of that access. If iron ore becomes more valuable, then the amount paid by UBI increases. Similarly, increases in land price translate to increases in UBI.

Even at full automation, Georgism results in a fairly balanced economy. People don't have any opportunities to work, but they still have part-ownership in all the land in the country, plus its other natural resources. They get payments based on that partial ownership, which translates to having enough money to still live comfortably. It's much more uncertain whether the current system of things in western countries would result in a balanced economy. It's quite possible that if western countries experienced a huge wave of automation, the current system would just be unable to handle it. There would be natural resource owners getting incredibly rich at the same time as there was mass unemployment. People would be poor and struggling to find work, despite having a strong desire to work and earn money.

So far, the conclusion is that Georgism is capable of handling increasing levels of automation much more gracefully than the current system. Automation is a good thing, of course, since it saves labour. However, it can have bad effects if the economic system isn't set up to handle it.

Above, we saw that international trade acts kind of like automation. Trading wheat for cars is kind of like having a machine that converts wheat to cars. So if we imagine a nation that suddenly starts engaging a lot more in international trade, that's probably a fairly similar situation economically to a nation that suddenly has a lot more automation. If the nation is Georgist, this should work out fine for them, but otherwise, they might struggle a lot with unemployment. Like automation, international trade is a good thing for a sensibly designed economy but could cause problems for a poorly designed one.

I suspect this is why protectionism is such a strong political idea. A large number of people sensibly realize that under the current system, international trade does not make them richer, but rather makes it more difficult for them to be employed. (There's also the usual pack of corporations and other special interests that would benefit from not having international competitors, but these ideas also have actual regular people supporting them, so that can't be the whole story.) People notice that international trade is going to make it harder for them to find work, and won't increase their basic income (because under the current system, they don't have a basic income) and they also notice that this is true of all their friends too, and they decide that they're against it. Economists should continue to expect this behaviour from voters until we have a system that more sensibly handles automation.